Meg Didier: From Survival to Advocacy - A Pioneering Heart Journey

Meeting Meg was mind-blowing. Her story, her life, and she herself are truly inspiring. I am honored to feature her interview as the first in this new series - Inspiring Others.

Imagine a person whose laugh lights up the room, whose energy is infectious. Her name is Meg Didier. She's the Director for Fontan Patients at Sisters by Heart and a co-founder of Single Ventricle Patient Day: Teens and Adults, hosted by the Fontan Outcomes Network.

In the world of Congenital Heart Disease (CHD), she's as famous as a rock star, with patients and mothers eager to take photos with her. I had never seen anything like it until I met her in Milan, Italy, at my first International Conference on heart-related topics. One mom even video-called her teenage daughter, a fan of Meg's, to say hi. I was amazed.

Meg is a true pioneer, an inspiration for us and our children, showing us what life can be. Before meeting her, I knew adults with hearts like my daughter's existed, but I had never met one in person. I was star-struck. Meg is one of the few people I've met who are incredibly easy to talk to. Her honesty makes vulnerability look easy, yet I can imagine she can be challenging for many medical professionals. She's someone who doesn't take no for an answer.

"I was born in 1991 in Norwich, a small town in upstate New York. The hospital there couldn't diagnose me, so after I was born, they sent me home, thinking I was healthy. At seven days old, my mom noticed I was breathing funny and struggling, so she took me back to the hospital. They said they didn't know what was wrong, saying, 'She looks like she's dying, something's wrong with her heart, but we don't know.' From there, I was taken to several hospitals until I was diagnosed with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. My parents were told they didn't know anyone doing well with this condition. One doctor advised that if I were his child, he would take me home and let me die through comfort care."

Thirty-two years later, not only is she alive, but her life has been full of breaking boundaries. She's setting new benchmarks for what's possible with a single ventricle heart.

"Eventually, I was taken to Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, where my parents learned that multiple people were surviving with this condition. We were misled by that previous doctor, which frustrated everyone. The two hospitals were not even five hours apart, and this kind of misinformation still happens today!"

At the time, "fixing" a single ventricle heart through a series of three surgeries to reroute the circulatory system was experimental. Her parents decided to fight the odds.

Rigby, M.L. (2023). The Univentricular Heart: Past, Present and Future. In: Clift, P., Dimopoulos, K., Angelini, A. (eds) Univentricular Congenital Heart Defects and the Fontan Circulation. Springer, Cham.

Her first open-heart surgery was at 11 days old, the second at 6 months, and the third (Fontan) at 13 months. At two and a half, she needed one more surgery, but since then, she remembers being allowed and encouraged to set her own limits.

"After all, this is why they do the surgeries - so patients, kids, can have the best quality of life possible. As my surgeon would say, they're taking a good heart muscle and putting it to efficient use. So why not have these kids live their best quality of life?"

For Meg, that meant becoming a high-level competitive gymnast. She entered the world of gymnastics at 14 and competed until she was 17 when she had to retire due to one too many injuries and broken bones.

"It was a huge shock because gymnastics was how I verified I was healthy. I thought to myself, well, if I can still do gymnastics, then my heart is still okay. Without it, I had to redefine who I was. I spiraled into a crazy whirlwind of emotions that led me to advocacy. Over the years, I started seeing some of the effects of my single ventricle heart. I had strokes in my early twenties and experienced afib [Atrial fibrillation = abnormal heart rhythm]. So, I wanted to be part of the solution, helping patients like myself have their voices heard."

Meg turned her life toward building up the community, training, educating, and equipping patients and families to be their best advocates. She wants them to understand their healthcare journey and live their best quality of life.

I often say a life with a single ventricle heart is full of ups and downs, though Emanuela's cardiologist might disagree and say it is not entirely true that with kids like her, 'there's always something.'

"This is exactly how I feel too. And my provider would probably say the exact same thing as yours. From a physical standpoint, it may not be a roller-coaster every day. However, from a PTSD standpoint, it feels like you're always waiting for the next shoe to drop. You feel you could have a stroke or a pulmonary embolism at any moment, or go into heart failure. It's hard when you have no control or insight into what this journey might look like."

Rigby, M.L. (2023). The Univentricular Heart: Past, Present and Future. In: Clift, P., Dimopoulos, K., Angelini, A. (eds) Univentricular Congenital Heart Defects and the Fontan Circulation. Springer, Cham.

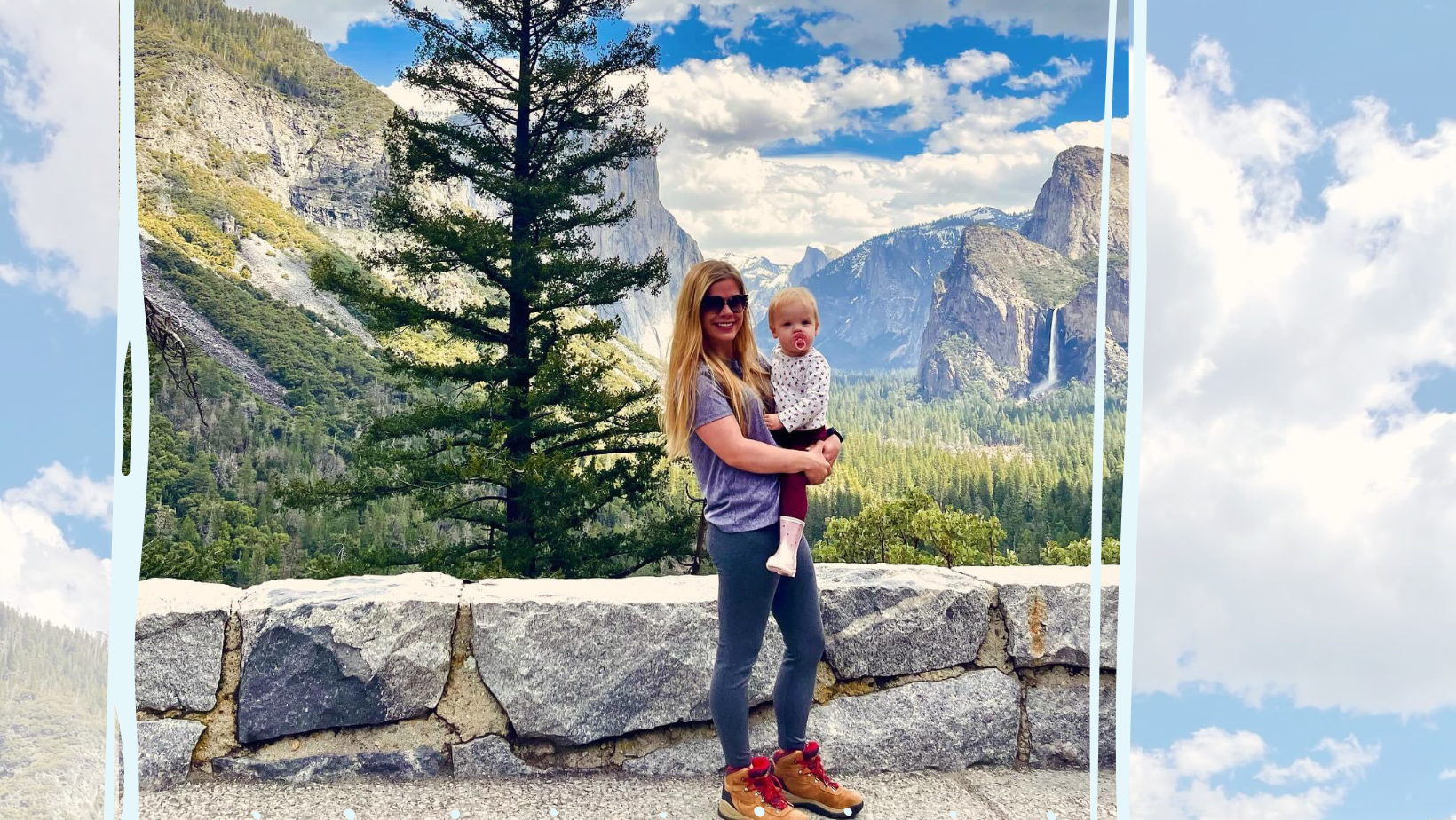

So, Meg decided to seize life. Her heart might have slowed her down, but it didn't stop her from doing what I believed, until I met her, was unimaginable for a person with a single ventricle. She danced, hiked, skied, and even became pregnant, giving birth to a beautiful baby girl.

As a journalist, I used to believe nothing was impossible - it was just a matter of wanting to achieve something and knowing how to. As a mother, that part of me silently drifted to the back of my mind as I found myself emphasizing what Emanuela can't or will never be able to do. Meg reignited that belief in me. She reminded me that with a tailored approach and the right support, anything is possible. Because, being healthy or not, is life without risks even worth living?

"I think I owe a lot to my mom. She never accepted 'no.' She always figured out a solution. For example, when I wanted to go skiing while on heavy-duty blood thinners, we talked to my team and figured out how to safely take a week off blood thinners. My mom's attitude was always, 'Let's work with it, not against it.' This mindset shaped my life."

Meg applied the same approach when she wanted a tattoo, which was initially a no-no for patients like her.

"I talked to cardiology, and they questioned why I'd want to do that. I lived through all of these surgeries. But why would anyone want to do anything? That's the question. Now we only get to do everything perfectly? Without ever taking any risk? That's not fun at all. I wanted to find a way to safely get a tattoo, with antibiotics beforehand and follow-up blood tests to check if there would be any spike in white blood cell count or whatever. It's about having an open line of communication with the care team and working together. One of my cardiologists jokingly said, 'Don't overestimate my ability to comply.' It was clear they knew I wasn't going to sit still. I will follow their advice, but it's my life, and as long as I communicate and we do things safely, that's my choice."

Being different and often slower doesn't go unnoticed by her, though. It's not about living in an illusion but living fully.

"Oh, absolutely. When I was ten, a coach told me being slower and running had nothing to do with my heart. Clearly, that's wrong. He dug at me and my heart defect, and that was hurtful. I always feel behind, especially in exercise, which impacts my will to try new things. But trying to navigate my own personal best is how I've been able to do anything, and to feel like I can keep pushing forward, which is hard sometimes. For example, I have a hard time hiking with anyone because I have severe anxiety over the fact that I'm behind. If I've hiked with you, it's because I trust you immensely. There's only been a few different people in my life that I've done that with. That's also why I think mental health is just such a massive point throughout this journey. There's so many aspects of our lives that are mentally driven."

We talked about the mental health of the CHD population and how parents can prepare their children for very probable challenges - lack of self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and finding purpose with an uncertain future.

Meg shared her first hospital memories and lasting fears and triggers. As a mother, I wonder what Emanuela will remember from her surgeries and hospitalizations. Many parents have this concern.

Thinking of my daughter being bullied for her scars or discriminated against for her invisible disease breaks my heart. Meg shared her experiences.

Survivor's guilt is another heavy burden. If I struggled as a parent, I can't imagine how patients feel, witnessing members of their community losing their battles while others live and thrive, without understanding why.

We talked for over an hour about all this and what the future holds for the first survivors, pioneering new paths for our children.

It is overwhelming and too important to fit into one post. So, stay tuned and SUBSCRIBE to be notified when I publish next.

I promise not to spam. You'll receive a notification of a new post once every two weeks.

Thank you for your support.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for informational or educational purposes only. It does not substitute professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified health provider.