The Privilege and Pain of Knowing: Our Prenatal Diagnosis Story

Receiving a prenatal diagnosis of a child's heart defect is not guaranteed. That is not to say it's impossible. Here's our experience.

Life was set out to be perfect. I had a career. I met a man. We got married. My life was about to be everything I had ever wanted: exploring the world and building a family. We always said children would not change us. I mean, we knew they would, but we made a pact that we would not be taken hostage by becoming parents. Children would enter our lives as we had built them, and we would continue to live that way, with them. The plan was in motion when a second line appeared on my pregnancy test.

It was a beautiful sunny day, like so many in Beirut, Lebanon, where we lived at the time. I was out of my mind happy. It had only been a few weeks after our honeymoon, and honestly, we were just trying our luck. And we got it – beginner’s style: bullseye on the first shot! I meant it when I said life was set out to be perfect!

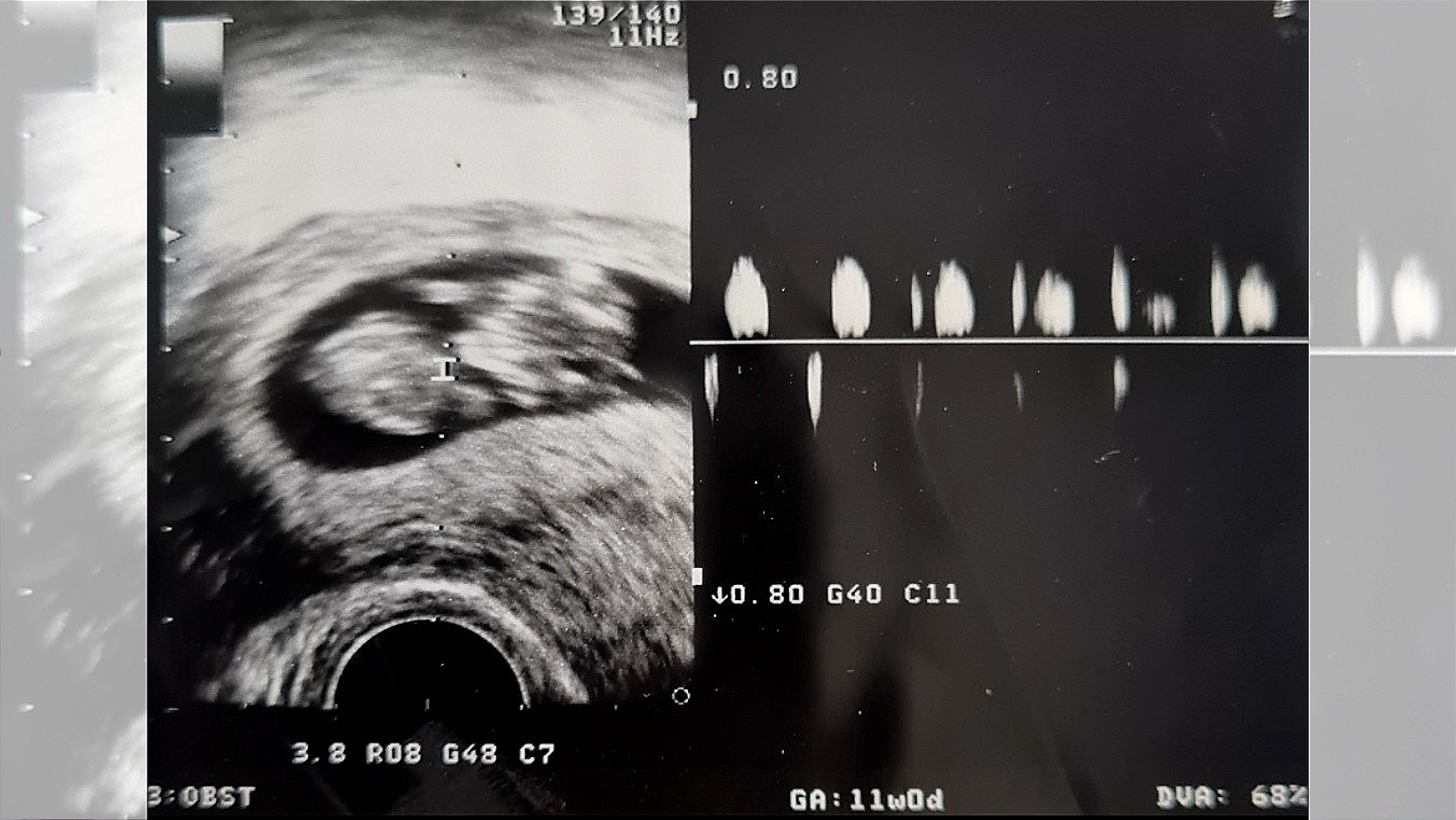

I was beyond impatient for my first appointment with the OB-GYN, to get it officially confirmed and start the ball rolling - celebrating, spreading the news, mom-to-be shopping, guilt-free eating, romanticizing... oh, nine straight months of daydreaming about our future, our lives, our family... All of a sudden, there it was, in real life – a little dot on the ultrasound screen. I was around seven weeks pregnant.

Bad News Coming

On the way to the second appointment, I stopped at my favorite pomegranate juice stall. We were one check-up away from the "safe to announce to everyone" moment. I was pregnant! I was living the dream! I felt like I owned the world. You know those people walking down the road with a "stupid" smile on their faces, untouchable, and you're just annoyed by them on a bad day? Well, I was one of those people! The sky was blue, the sun was bright, everyone was rushing somewhere, the Middle Eastern traffic was loud, and all I had to do was go to the doctor's office to see how my little plum was doing. And yes, I had the app that told me the size of my unborn baby each week and compared it to a fruit. I loved it all! And as I'm writing this, a thought crosses my mind... in a way, getting struck by lightning when flying so high - makes sense.

"It looks as if the heart might not be developing as it should," the obstetrician said after an hour of staring into the monitor, moving the ultrasound stick around my belly, pressing into it, applying the gel that gave me chills, and silence.

I must have hummed something in my head during that hour, staring at the ceiling. Expecting nothing. I was clueless, all romantic about the whole process. I mean, there would be a baby!

What is he talking about? I remember thinking, feeling my heartbeat in my throat, saliva filling my mouth, fear flushing my body, my eyes burning because I forgot to blink. I remember all of that vividly because I feel it just the same now, as I am writing about it. And then, words of immense relief and hope:

"It is still early," he continued while I was turning numb. "Maybe it's just a technical problem, maybe only a shade, I'm not sure, but I want to be. Come back in two weeks."

I was 12 weeks pregnant. By the time I walked to the 14th-week ultrasound, I had lost the stupid smile.

The Lucky Ones

Less than a year later, as the Children's Cardiac Center and the hospital in Bratislava, Slovakia became our second home, I got to talk to many mothers who had no idea their baby would be born with a heart defect. It seemed like we were the lucky ones.

So, while mothers-to-be are nesting, daydreaming about the love of their lives they are about to meet, and stressing mostly about the act of birth, approximately six out of ten of those who are about to give birth to a medically complicated child are completely clueless about what's to hit them.

Although the official statistics vary by country, it is safe to conclude that receiving a prenatal diagnosis of a child's heart defect is not guaranteed. There are many factors to consider - some defects are difficult (or even impossible) to detect in utero; some doctors may lack the knowledge of what to look for; and some hospitals may not have the latest technology and equipment available. However, this does not mean that it is impossible to discover before birth that the baby will be born with a special heart.

None of our doctors from the second, third, or fourth opinion hunting believed it was possible for us to know there was a problem already at the 12th week of pregnancy. I was told not to worry when requesting appointments to verify the diagnosis. So we waited.

1 in 100

All those stories I was told in the weeks between the first hint about a possible major problem with our baby's heart and the regular first-trimester anatomy scan, about “doctors having it wrong all the time” and “mothers giving birth to healthy babies against all odds”, were building my hopes, albeit on a very shaky basis. The 20-week scan crashed that house of cards into an unimaginable emotional mess.

It was clear that our firstborn would have a serious defect – a single ventricle heart and a transposition of great arteries. At least. We had months to prepare for a life... less than perfect.

My first online search was overwhelming.

https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/congenital-heart-disease

I couldn't read through tears anymore. But I kept going…

As our Emanuela was winning her battles during those first seven months of her life in the hospital, and as I started to regain control of my thoughts, I found myself becoming angry. No mother should come home empty-handed after giving birth because no one told her during any of the numerous prenatal check-ups that her baby might be born with a serious heart problem.

Prenatal examination of the heart should be part of the prenatal morphological ultrasound, which is performed at week 22. It can be done even earlier (between the 11th and 13th week) with a very good result of an experienced prenatal diagnostician.

(MUDr. Matej Nosál, PhD., chief of cardiac surgery at the Children's Cardiac Center in Bratislava, Slovakia)

MUDr. Matej Nosál', PhD., chief of cardiac surgery at the Children's Cardiac Center in Bratislava, Slovakia, talked about this problem in a podcast for www.preventivne.sk. You can find an excerpt in our Expert Answers folder (in Slovak language).

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for informational or educational purposes only. It does not substitute professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified health provider.